During the Interbellum years, the US Army did not offer a spectacle program for soldiers. Each man was expected to furnish himself with eyeglasses if he required them, although momentum was building amongst senior officers to develop an Army spectacle issue program, particularly from the Surgeon of the IV Corps Area at Fort McClellan, Alabama, who recommended that the Army provide soldiers free replacement spectacles. The recommendations ultimately led to many unscrupulous claims, but it soon became apparent to the War Department that training would cease entirely if the soldier was unable to see!

The Surgeon General duly took the proposal forward to the War Department, which agreed in 1941 to provide spectacles to all active duty soldiers who required them. As a result, The Surgeon General's staff set about estimating requisition requirements for the program, but it soon became apparent that such a task was almost impossible given the lack of usage or issue records from World War I. As a result, they seemingly plucked a figure out of the air, and estimated that 10% of military personnel would have sufficiently defective vision to require permanent correction, and also made the assumption that half of these soldiers would enter the service with their own spectacles. Based on these assumptions, The Surgeon General's Office estimated that 200,000 pairs of spectacles would be required on hand in 1942.

Portrait of Chaplain Fred McDonald. Fred collected fragments of glass from bombed and bullet-riddled churches throughout Europe and brought them back to the US after his service ended. His P3 spectacles can be clearly seen.

It soon became apparent, however, that allowances had not been made for broken or misplaced eyeglasses; or for the fact that most men who entered the service with their own spectacles owned glasses that could not withstand the rigorous army life! Indeed, the Medical Department discovered that in actuality, between 18 and 20% of personnel required corrective lenses, and in 1943 issued in excess of 2,000,000 pairs (a ten-fold increase of the original estimate). This ultimately led to the lack of an Army optical program being ironically branded as "short-sightedness" in a report prepared by Silas B. Hays, Louis F. Williams, and Robert L. Parker of the Planning Division, ASF. Rather than costing $150,000-$200,000 a year, as originally estimated, the optical program was actually costing $8-$10 million a year by the fall of 1942. At the same time, the War Department had issued regulations stating that each individual needing spectacles for the efficient performance of his military duties was to receive one pair as soon as possible after induction and a second pair when he embarked for overseas duty.

Since it has now been established that the US Army issued all eligible personnel with spectacles, it should come as no surprise to learn that it is the responsibility of the bespectacled living historian to source accurate eyewear for their impression!

P3 spectacles, manufactured by the American Optical Company in their issue case, made of olive drab leatherette. Of interest is the cautionary note attached to the lid of the case warning against damage or loss of spectacles.

(Author's Collection)

"Ful-Vue" P3 Frames

After determining the requirement and basis of issue for spectacle supply, it became essential for The Office of the Surgeon General to identify and procure a frame design suitable for military personnel. Following extensive testing and laboratory examination, the choice was ultimately a metal of 10 percent nickel silver, with reinforced bridge constructed to withstand rough usage. It would later be discovered that this particular material was undesirable in warmer climates as it corroded easily where it came into contact with the skin, and in some extreme cases caused discolouration and dermatitis. These later findings led ultimately to an increase in the nickel silver content to 18% and by constructing the pad arm, pad arm assembly, endpieces, and cable windings of pure nickel.

Overview of a pair of P3 spectacle frames, complete with lenses. This pair was manufactured by The American Optical Company, Illinois.

(Author's Collection)

The concept of an Army Optical Program had excited the markets, and once it was officially announced, the Government received numerous bids from optical companies throughout the United States. However, of all the companies vying for the contract, only the American Optical Company and Bausch & Lomb Optical Company had dispensing facilities throughout the country. As the lowest bidder, the American Optical Company ultimately received the contract to furnish the Medical Department with ready-made spectacle frames, but within a few months of production, it became evident that AO could not supply either the frames or lenses in sufficient quantity to meet the increased demand, resulting in a contract for lenses being issued to Bausch & Lomb, and additional contracts for spectacle frames to be apportioned among nine manufacturers on the basis of their production.

Despite the standardised material, the requirement for multiple manufacturers ultimately led to the standardisation in frame design for military procured spectacles. During World War I, a "Windsor" frame design (American Optical 5486) was a popular choice, but its design did not facilitate sufficiently-large lenses as required by the War Department during World War II. As such, The Surgeon General settled on the "P3" design, marketed commercially as the "Ful-Vue". The P3 frame made use of a larger, round lens which could be produced by mobile optical units relatively easily, and increasing the overall peripheral vision of the wearer. The P3 also featured nose pads and riding temples which improved the frame's rigidity and emplacement in the field.

The "P" in the acronym stands for pantoscopic, simply that the top part of the lens is tilted slightly forward (presenting the advantage of reducing glare and enabled opticians to more precisely correct vision). The "3" references the fact that the width of the lenses is three millimetres wider than the height.

Suffice it to say that if you're looking for accurate eyewear for your impression, the accuracy of the "P3" cannot be argued; it was issued to all troops after all... at least, in theory.

A selection of spectacle cases issued to the GI. The overall design is consistent, featuring a sprung lid closure and covered with leather-effect vinyl. The colours shown here seem to be the most commonly found (olive drab, black and dark green).

(Author's Collection)

Civilian and Commercial Frames

Despite the Army's best efforts and financial commitment to its Optical Program, it was plagued with supply and delivery problems from the very beginning. The initial underestimate of The Surgeon General, coupled with the huge increase in the rate of inductions during 1942-1943 impeded the Optical Program immensely. According to official contemporary figures, it took approximately 5 months to source materials, process the frames and lenses, and ship them to branch offices; figures that could not be easily scaled with draft increases. Although it was a stipulation in issued contracts that spectacles would be delivered no later than 3 days after receipt of an order, it was not unusual for deliveries to be delayed as much as 3 or 4 months. Indeed, in some extreme cases, recipients of spectacle prescriptions had completed their training and already posted to overseas duty before receiving glasses that had been ordered during their basic training!

The problem was further compounded with overseas issue, in many cases the spectacles were delivered after the soldier had left the camp in which he had been examined; in these instances, the glasses were forwarded to his next post, only to arrive after his departure. Indeed, in some instances some troops never received their spectacles; some had spectacles delivered to them at a place and time so far removed from the eye examination that all memory of the refraction and the prescription had been erased from their minds.

T/Sgt Meredith J. Roger (San Antonia, Texas) of the 2nd Infantry Division, proudly shows off his lucky escape. Photograph taken near Cherbourg.

As a result of these supply issues, it is not uncommon to observe soldiers wearing civilian or commercially procured spectacles, and living historians can replace the more common "P3" design with any contemporary frame design. It is important to note, however, that AO were furiously marketing the "P3" design in the Interbellum period, and a great many of American civilians made the switch from the earlier Windsor design. As such, the overall design should be close to the P3 frames illustrated in this article, but the material and temple design can be varied if they are unobtainable. Indeed, studies of contemporary photographs show that the vast majority of soldiers in the ETO can be observed wearing P3-design frames.

Photographic Study

The following contemporary images showing the use of P3 frames amongst American GIs during World War II. Click on an image to enlarge:

Gas Mask Inserts, M-1

Unlike the British Army, which issued specially-designed spectacle frames which could be comfortably worn underneath the service respirator, the US Army's decision to issue commercially frames presented another technical problem; the use of eyeglasses with gas masks.

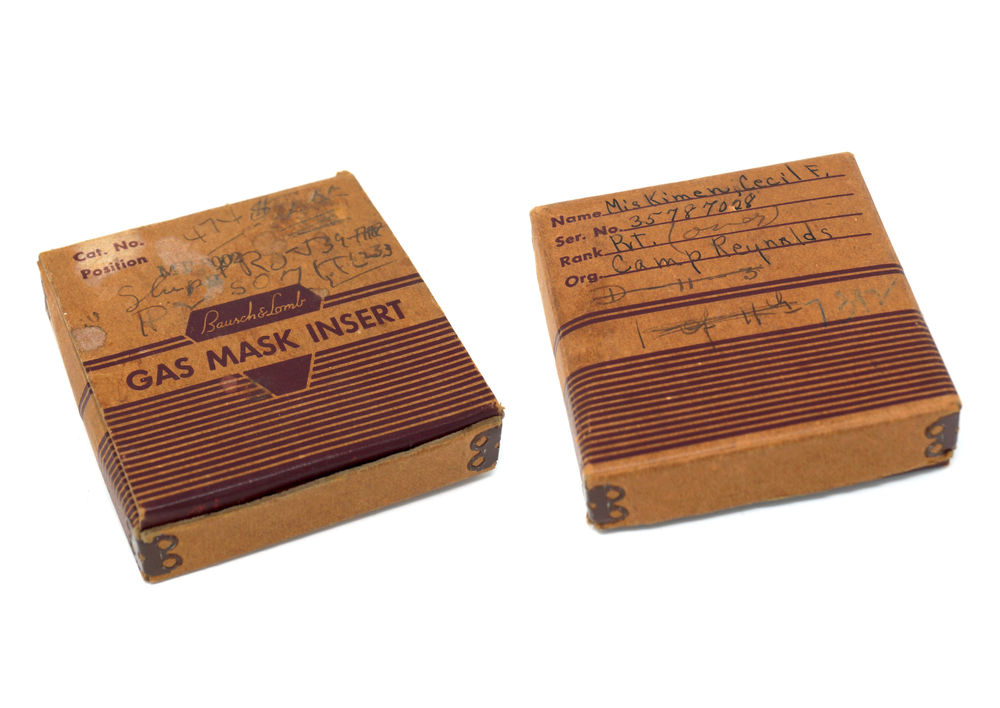

Overview of the box in which M1 Gas Mask Inserts were provided to the individual serviceman. This example was issued to Pvt. Cecil F. Miskimen (ASN: 35787028).

(Author's Collection)

The German and Japanese military had already tackled the problem by issuing spectacles that were secured to the head by means of an elasticated strap, thus removing the issue of the troublesome hinges. When the US Army Medical Department was tasked with developing eyeglasses for use with gas masks, both the British and Axis counterparts were considered. The Axis-style was rejected as unsuitable, for the elastic band forced the bridge of the goggle frame too severely against the nose, causing great discomfort and it was also discovered that it caused a leakage at the temples. Eventually, the British-style design was adopted and extensively tested. At first, it was directed that all individuals requiring visual correction be furnished gas mask spectacles when they moved to a staging area or a port. On this basis of issue, the requirements were very high, while the period of time for issue was so short that many men were shipped overseas without the spectacles. Regulations were soon changed to provide that only those individuals with a binocular visual acuity of 20/70 or worse would be furnished gas mask spectacles; these men were to be fitted when their unit was alerted, which allowed 4 to 12 weeks for prescription and issue.

Although there were some initial problems in fitting of the procured spectacles, a far bigger problem soon presented itself. When the newly-introduced spectacles were worn underneath the mask, it could not be completely closed, and a leakage at the temples was produced. It is unclear why such a severe defect was not identified sooner, and by the time the Medical Department and CWS had identified it, in excess of 100,000 pairs had already been procured and issued. As a direct result of immediate testing, a directive was issued prohibiting the use of the eyeglasses with the gas mask, and prescribing that already-issued spectacles should be employed as an auxiliary pair for ordinary wear. The overall result of this affair meant that the US Army still lacked a suitable design for gas mask spectacles as late as August 1943.

Detailed view showing a pair of M1 Gas Mask Inserts, manufactured by Bausch & Lomb.

(Author's Collection)

By the summer of 1943, combined efforts between the Medical Department and CWS saw the prompt development of “gas mask insert”, officially designated as Eyeglass, Gas Mask, M-1 (Medical Department Item # 9362400). It was accepted as a new standard almost immediately after limited testing, and while it was procured and distributed in large numbers, was never considered to be more than a satisfactory makeshift. Despite this however, there were no more attempts to develop a more suited solution; the Medical Department hoped that the Chemical Warfare Service would ultimately design and adopt a gas mask with which the commercial-type spectacles could be worn. However, this hope never received any encouragement.

The M1 Gas Mask Eyeglasses consisted of a wire frame which held the lenses which was supported by three brackets and attached to a frame inserted beneath the gas mask next to the lens. This particular design presented numerous problems with fitment, far more complex than those encountered with the commercial-style spectacles typically issued by the Medical Department. The issue was slightly overcome later in the program by the adoption of a simple, plastic guide which could be marked with the standard positions of lens placement and adjustment.

Detailed photograph showing an interesting label affixed to a spectacles case issued to a GI. Despite their being no official evidence that the P3 frames could be suitably worn with the Gas Mask, this pair have explicit instructions on how they should be properly adjusted!

(Author's Collection)

Gas Mask Inserts were eventually issued in the same fashion as the original gas mask spectacles. Personnel alerted for overseas movement and who had visual acuity of 20/70 or worse were supplied with the inserts. Realistically, this meant that approximately 7 percent of all Army personnel were issued with Gas Mask Inserts, and the Medical Department estimated an annual maintenance / replacement factor of 30%. Overseas distribution of the Inserts proved far more difficult than anticipated since by the time they had been developed and procured, a large number of US servicemen were already overseas without suitable spectacles for use with the gas mask. Although every effort had been made to ensure that adequate supplies were eventually furnished to each Theater of Operations, it is evident that uncorrected visual defects would have greatly weakened American fighting forces, had gas warfare been employed during this period.

Sources of accurate frames

Thanks to the power of the Internet, it is now easier than ever for re-enactors and living historians to source original or accurate reproduction frames to complete their impressions. Most local opticians will install prescription lenses into your own frames if you ask (but be prepared to sign plenty of paperwork waiving any damage that may result in the frames).

The following list of vendors may be of assistance in locating suitable frames for your World War II GI impression:

- Eyeglasses Warehouse (US)

- The Vintage Optical Shop (US)

- Dead Men's Spex (UK)

- eBay (global)

Acknowledgements & Sources

The following primary, secondary and tertiary sources have been used in the compilation of this article, and are included below as a matter of completeness and interest to the reader:

- Ellis, M. (2012). Four Eyes: Eyeglasses and the WWII GI.

- Gawne, J. (2011). Spearheading D-Day : American special units in Normandy. Paris: Histoire & Collections ; Newbury.

- Heaton, L.D. (1968). Medical Supply in World War II.

- Richard (1997). The History of the U.S. Army Medical Service Corps. Defense Department.

- LIFE Magazine Archive

The author would also like to express his thanks to Adam Berry for kindly providing some of the contemporary images that appear in this article.